PART-TIME NOMADS: Learning How to Travel the World by Bicycle

Part-Time Nomads, released 27 September 2023, WOO HOO!

Also available in several San Francisco bookstores: Browser Books on Fillmore, Russian Hill Bookstore on Polk, Dog-Eared Books on Valencia and Bird & Beckett on Chenery.

Bookshop.org:

https://bookshop.org/p/books/part-time-nomads-traveling-the-world-by-bicycle-anne-m-breedlove/20619456?ean=9781631322037

Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/Part-Time-Nomads-Traveling-World-Bicycle/dp/1631322036/ref=sr_1_1?crid=3CA1P6B0WWCNT&keywords=part-time+nomads%3A+traveling+the+world+by+bicycle&qid=1695839265&sprefix=part-time+nomads+traveling+the+world+by+bicycle%2Caps%2C125&sr=8-1

Barnes & Noble:

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/part-time-nomads-anne-m-breedlove/1144102780?ean=9781631322037

Better World Books:

https://www.betterworldbooks.com/product/detail/part-time-nomads-traveling-the-world-by-bicycle-9781631322037

Blackwells:

https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/9781631322037?source=65769¤cy=USD&destination=US&a_aid=65769

https://www.valore.com/vb/cart/addItem?site_id=U1VGnq&product_id=71936423&listing_id=&sellerMarket_id=1029654349&shippingType=Standard&condition=New

https://www.textbookx.com/single_product.php?product_id=2329212886&action=buy&affiliate=cj-generic&PubID=284433&cjevent=7ff738da5d7011ee8270011c0a1cb825&utm_channel=affiliate&utm_source=CJ&utm_medium=13th+Generation+Media&utm_campaign=API+Link&utm_term=&utm_content=200105384041946850%3AcfcgjUfRB2H0

Find me on IG: @speedyab6

Here’s a sneak peak, Chapter 2:

Here’s a sneak peak, Chapter 2:

Our first solo bicycle tour in the Sacramento Valley exposed a few wrinkles in our quest to becoming Independent Bicycle Travelers. One of the hardest was the realization that California is not rural France. The hills of the Dordogne were fun but they are just that, hills. California is bigger, higher, steeper, harsher, and bolder. Cycle touring on our own home turf was more difficult than we expected.

After hours of research and tire kicking, Jim dragged me with him to check out and okay his choice of tent and sleeping bags at REI. While he will allow me a veto, I mostly trust his judgment. I know my limitations; I’m neither an equipment person nor a shopper, both bore me to tears. On the other hand, although Jim loves guidebooks, he finds maps and detailed route-planning tedious. Mr. Spontaneous prefers to just let things unfold. Slowly, we learned that we made a pretty good team and realized our good fortune at our compatibility.

Radiantly happy with his new purchases, he surprised me on the way home, “Let’s test them out in Livermore. It’s only an hour drive south from here. We can drive down Friday morning and come back the next day. There’s a campground on the eastern side of Mount Hamilton.” He remembered seeing a sign years ago, back when he was a Weekend Warrior. “Look it up, it should be a manageable distance from Livermore.” A Native Californian, he knew a lot more than I did about the nooks and crannies of the East Bay.

Sure enough, Stanislaus County had a campground, Frank Raines, named after a county supervisor who died in 1953, the year the campground was dedicated to him. That says something about the guy, getting his name in lights that fast after buying the farm? Jim wanted to just head south from Livermore and ride the same route back again.

Ugh, I thought. I’m a looper—I always prefer to do a loop than an out-and-back. So I studied the maps some more and found the California Aqueduct/Mendota Canal in the San Joaquin Valley had an access road. I found Jim in the garage working on the bikes.

“Jim, how about we make the ride a little more interesting, make it a loop?” I suggested. “What if we went out Tesla Road to the valley? The canal has a frontage road and we can turn west at Del Puerto Canyon Road.” I mumbled, “It’ll add some miles, though.”

“More? You want to make it longer, our first time loaded with the tent? I dunno . . .”

“Yeah, but good news: it’s flatter. Mines Road climbs to 3,000 feet; the canal route is only half that.”

“Half, huh? Okay, I’m game, if you say so. But it’s your ass on the line.”

Tesla Road was mostly isolated rundown ranches, the transition to today’s (sniff) Hoity Toity Wine Country was only just beginning. The first few miles along the canal were laid back. We were on hard-packed dirt on the top of a levee with a view in all directions. To the far west was the spring-green Diablo Range we just cycled through, at the base was a strip of brown farms, and next came the bustling Interstate 5, a blur of cars and trucks racing north and south. Last was the cold blue-gray water of the California Aqueduct, with us riding on the levee. From time to time, we caught a glimpse of the parallel Mendota Canal on our left, which occasionally got within a half mile of us. Then came more farmland, and far to the east, the Sierra Nevada which lead to Lesson #6: Cycling Along Water is Dreamy. But we found it wasn’t all dreamy—after a couple of miles, we encountered a locked gate across the levee. Ugh, we had to take off all our gear, portage it over the locked gate, then load up again. And it happened four times. Although the Aqueduct flowed all the way to Southern California, we left it after twenty miles to turn west, thank goodness, stopping at a gas station in Patterson on Highway 5 for ice cream and cold drinks.

After climbing another nine miles back into the Diablo Range, we arrived at a completely empty campground just before 1 p.m. on a Friday. We set up our tent and checked out the facilities. The 1950s-era, cinderblock building was well maintained, clean, and had unlimited hot water showers; pretty posh for a county campground. Because it was still early afternoon, we decided to stash our gear in the tent and ride unloaded up the canyon to San Antonio Valley Road, noted for its fields of wild flowers, especially in spring. We knew we couldn’t make it all the way to the top of Mount Hamilton, that was another thirty-five miles and four-plus hours because the climb was 4,000 feet plus. We’d try that if/when there was a next time; it would require staying two nights in the campground. This trip was a one-nighter, just to try out Jim’s new tent.

We clipped along up the unpopulated valley—farmhouses were very few and far between—the fields awash in blue and violet, orange and white blooms. It was so pretty, so worth the extra miles. But we had another motive. The guidebook said there was a restaurant, the Junction Bar and Grill. Truly in the middle of nowhere, it survived on the odd ducks who made their way to this remote corner of the Bay Area, at the junction of three roads leading to Livermore, Patterson, and Mount Hamilton. We’d packed only nonperishable food, so a restaurant meal was irresistible.

We pulled into the dusty parking lot and leaned our bikes up against the post in front of a big picture window. Even so, Jim still locked the bikes. The place wasn’t too busy, the weekend crowd probably didn’t start for a few more hours. There were four motorcyclists, several birders in regalia rivaling the birds’ plumage, and a couple of local old-timers stopping by for news, mail, and cold beers. The long room had a huge volcanic-rock fireplace in one corner, a hammered-copper bar, and a walk-in refrigerator behind the bar filled with bumper stickers and decals put up by customers dating back decades. “Real Cowboys Don’t Line Dance.” “Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History.” “For kicks, see a rodeo.” We ordered the American staple of burgers and fries. It was not great but not terrible. If the fries are hot and crispy and the burger pink, I’m happy. Plus the beer was on tap.

It didn’t take long for an across-the-room conversation to get started. Lesson #7: Travel Cyclists Attract Mosquitoes. That’s what Jim came to call the people who can’t resist asking the three questions: Where are you from? Where are you going? and, How fast do you travel? Most people fall into one of two groups: the first group thinks we’re crazy and wants to keep a wide berth in case we’re contagious or, worse yet, ax murderers. This was a hard connection for me to understand. I mean, how many news headlines have you read that said: “Infamous cycle touring/ax murdering couple caught while trying to escape on road outa town”? The second group also thinks we’re crazy but wants to learn what makes us do this in order to cure us and get us back into a car, RV, or at least, on a motorcycle.

The restaurant was quiet enough that when the youngest of the motorcyclists caught my eye. He asked, “Where are you going?” and everyone heard him.

Jim cringed as I answered, “Frank Raines campground.” Jerry introduced himself and volunteered that they just rode over Mount Hamilton from Gilroy. Then the female birder piped up, “Oh, that campground is too noisy to enjoy.” Next thing you know, someone asks, “Where are you from?” And when I say “Martinez,” well, one of the bikers knows someone whose sister lives in Martinez. Jim’s body language tells me he want to get out of there ASAP as the conversation starts bouncing around the room. I loved it—meeting new people and chewing the fat with strangers. Jim, not so much. He’d tolerate it as long as he either didn’t have to talk too much or if he got to talk about equipment. Then he lit up. Usually, equipment talking occurred outside, standing around the bikes with comments about components.

Speaking of equipment, on a narrow hairpin turn on our way back to the campground, we came across a splayed and shattered red Ducati motorcycle in the dirt on the shoulder just past a long black skid mark. It wasn’t there on the way up, that’s for sure. It looked totaled. We assumed someone had transported the driver to a hospital. We soberly looked at each other, reaffirming the need for care on these back roads. We never found out the story.

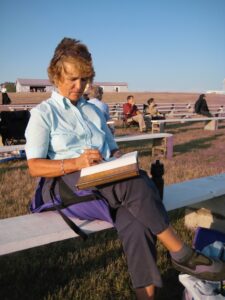

When we returned to the campground at 5 p.m. the place was packed—bedlam! Every spot was taken and filled with campers and utility vans of every size and shape imaginable. Big campers, RVs, vans, trailers. And the din of motorcycles came down from the hills just beyond the campground. The campground has a huge off-road vehicle park just adjacent. And that weekend was an annual Trial Bike competition. The campground was filled with families. I wished I packed our camera, but it was a monstrous number, the Pentax K-1000, hard to justify carrying. Turns out, trial bikes are uniquely designed small motorcycles that don’t have seats because the drivers must stand to execute the physical maneuvers. Who knew? And this competition was “fun for the whole family”—there were competitions for adults and children, boys and girls, even kids as young as four were eligible to compete, and some did.

The whole place sparkled from the sun shining on so many metallic surfaces, except for our forlorn campsite. Not one behemoth piece of machinery in it, the driveway completely empty, our two bikes locked to the end of our empty picnic table, and a tent only tall enough for sitting staked in the grass. We were embarrassed by the dramatic difference. The campsites were first-come, first-served but we somehow felt we had “stolen” a spot from a trial bike family. We were pretty much ignored as we sheepishly made our way to the showers. It was clear that except for us, everyone knew everyone; this was a big deal event that felt like a reunion.

Our campsite was near a grassy little mound that was popular with the under-four set—the kids too little to compete. Over and over again, they pushed their hot wheels up the slope, glided down and rolled over in the soft grass, which I imagine would be worn out by Sunday. Oh, I wished I had brought our camera.

Even though we had eaten, we were hungry again and laid out our pathetic spread on the picnic table: homemade sandwiches, nuts, fruit, and to compensate for the meager spread, we had a big bag of Doritos and a small bag of Pepperidge Farm cookies. Just as we were about to start eating, our neighbor, a perky blond, forty-something woman in a team T-shirt, denim shorts and sun visor carrying a steaming covered casserole, stopped, looked at us, and said, “Hey, we’re having a potluck in the Pavilion. Why don’t you join us?”

As Jim tried to disappear under the table, I replied, “Oh, but we don’t have anything to share.”

She tilted her head, rolled her eyes and said, “The kids love Doritos, and you two look like you could benefit from something more substantial. Come on over, it’s a lot of fun.” and hurried off.

As she walked away I turned to Jim, “Whaddya think? Should we go?” Jim gave me that look I long ago became familiar with. Cornered, he would much really rather not, would never choose to socialize with strangers, but he knew I wanted to; the invite was catnip to me. Plus, it would be churlish to say no, he knew it and I knew he knew it. I got a wickedly happy grin and clapped my hands—a party, we were invited to a party. Well, technically a potluck.

After shaping my newly opened bag of Doritos into a bowl on the potluck table, we filled (their) paper plates with their piping hot food, and sidled ourselves to a far corner table, where we could enjoy their show from a distance. It was such fun watching these enthusiastic, happy families. Ellen, the woman who invited us, stopped by. She lived not too far away in the valley, had three boys, eleven, nine, and seven, said they’d discovered trial biking through neighbors a few years ago. All five of them loved it and competed. She said their whole lives changed once they discovered trial riding. There were events year round in California and the Western states so they bought an RV and trailer to get to them. She noticed our meager plates were already empty. “Don’t be shy, go back for seconds. We’ll have lots of leftovers.” After a lighter second serving we left early and fell asleep just past dusk to the sound of happy campers and squealing kids.

We had to cover about fifty miles the next day to get back to the car, and even with the night’s lovely bonus dinner, we knew the next day’s breakfast and lunch would be ho-hum, with no options for a cooked meal until we got to Livermore. At first light, we climbed out of our tent and quietly broke camp as a few early birds made their way to the facilities. We left so early none of the campers nearest us were up and out yet, but we figured within minutes of our departure, some family would fill in our campsite. As we passed the closed Junction Bar and Grill, Jim said, “For our next trip, let’s buy some cooking gear, and two front panniers for me to carry it. Lightweight, of course!” My growling tummy made me realize he was right; cycling and cold food weren’t a good combo. But the weight of all that stuff—there had to be some limit to what it was wise to carry.